Workers' Control #3: Workers’ Control in the Public Sector: The Transport Workers Union Local 100 Experience

Mea culpa… I planned to finish on workers’ control with this post, but realized I wanted to provide some concrete examples of workers’ control struggles in the New York City Transit Authority from my forthcoming book, The Fall and Rise and Fall of NYC’s Transport Workers Union, 1975-2009. I think these partially re-written excerpts illuminate both what might be achieved even under pretty adverse work and management conditions – and then, how quickly those successes can be lost.

First Union Efforts at Workers’ Control

If, as I claimed in my last post, management wants control even more than productivity, it might seem particularly difficult to augment workers’ control in the public sector, where, in all but a handful of states, it is illegal for workers to strike or engage in job actions. Further, Joshua Freeman, the first labor historian to write extensively about the Transport Workers Union Local 100, hit the nail right on the head when he wrote that “an autocratic style of management seems built into the DNA” of the Transit Authority. Yet my experiences as a NYC transit worker, and the information I gathered while researching my book, shows that various measures of workers’ control were achieved and achievable. Some gains were facilitated by the specific organization of workplaces and work procedures; others rested more on the ability and inclination of the union to fight management dictate.

In its first years, TWU’s victories both at the bargaining table and in transit workplaces transformed the lives of its members, so much so that workers characterized the changes the union brought as a release from slavery. Alongside improving wages and benefits, the Local leadership focused on reducing working hours and so-called “split shifts” with unpaid time in between rush-hour work, and implementing policies on seniority and job selection. Later, though, the union’s leadership, many years off the shop floor and largely insulated from member sentiments, rarely endorsed workers’ control struggles, and sometimes even sabotaged them, trading control for (never very much) money.

Rather, it fell to shop stewards, lower-level officers immediately accessible to workers, and other shop-floor activists to take the initiative in the workplace. They ignored prohibitions against job actions. They negotiated informal agreements superseding and improving upon contractual terms. Workers saw that collective action was effective in addressing all the physical and psychic ways that life on the job could be improved.

Workers’ Control at 207th St.

I personally witnessed a pretty extraordinary level of workers’ control over production methods at the 207th St. (subway car) Overhaul Shop when I entered Transit in 1984. By strictly enforcing each worker’s job selection rights the union could also police the pace of work. Following a semi-annual system-wide seniority job pick, some work crews held a one-time “shape-up.” For example, a metalworker might pick the job “207th St.; Sheet Metal Shop.” In seniority order, the dozen workers in that crew “closed ranks,” selecting which machine each would operate for the life of the pick. The senior man, Meyer Singer, with over 40 years on the job, “owned” the brake (which bends metal). He could be “dropped” from his job and sent to a different machine or task if he had no work or if there was priority work in his trade elsewhere in the crew or shop. But then no other worker could “backfill” his job, i.e., work on his brake, in his absence. On the other hand, if that metalworker picked into the self-explanatory Wreck Gang, where the crew’s work varied from day to day, they participated in a daily seniority “shape-up,” run by the shop stewards, of available work. Whether the job they chose took a day or three weeks, they owned it until its completion. Seniority shape-up protected workers from victimization by supervision and was the first line of defense against speed-up.

By the time I came to the shop, routines had largely been established: worker, union, and supervision understood the stint, the amount of work, that was expected. Foremen mostly facilitated production, addressed bottlenecks, acquired needed supplies, and coordinated with supervisors of other work crews. But sometimes, in a steward’s or worker’s opinion, a job was understaffed, or was being rushed If a steward could not resolve this with the crew supervisor, the problem went up to a member of the union shop committee who conferred with shop management. If the dispute still could not be fixed, the steward or the committee might ask the whole crew to slow down.

So, trouble over one job would spread to ten; suddenly, subway cars that had been scheduled to leave the shop that afternoon were not ready. Or the pain could be spread even further: the union could find a work location elsewhere in the shop where management was offering overtime work to meet service needs, and ask the entire work crew to turn it down – to enlighten management to the error of its ways. Mass refusal is technically a violation of New York’s anti-strike Taylor Law, but the realistic prospect of shop-wide action in response simply made that kind of enforcement too perilous for management to contemplate.

Slowdowns and refusing overtime could also be applied to the problem of a confrontational supervisor, perhaps someone who had transferred in from another shop where management expected men to jump, or work faster, just because they were being watched. Or suppose a foreman dropped Singer’s brake job and sent him to fill a day-long vacancy in a different work crew. Suddenly, half-way through the day, a car might need a piece of metal bent to specification. The foreman would ask another worker to fabricate that piece. Sometimes a work crew would let little violations go – one hand washes the other. But what if the job actually took several hours? Or the foreman did not seem to be acting in good faith? How do you teach him a lesson? Perhaps the whole crew has to stop work and have a long meeting to discuss the matter with the steward, then cluster around the steward and the foreman. Maybe a committeeman would come down from the union office and fetch the foreman’s supervisor to make the point that, now, all production had come to a halt. Usually, the foreman would get, and remember, the message.

Workers enjoyed this, and they benefited from the power of their union. For those who shaped up daily, the 60 minutes between the start of each shift and coffee break were spent picking a job, assessing it, and acquiring the right tools and parts. In reality, that 15-minute break often ran twice as long as scheduled; some workers went outside to a coffee truck, but most bought their food from co-workers who had set up refrigerators and grills in the shop to make a few bucks on the side. Lunch also ran long, and usually workers had finished their work an hour or so before the end of their shift.

The key to enforcing these working conditions was union power – a combination of organization, planning, history, and volition (of the committee and workers) to wield it – and an understanding of the pressure points on management priorities. In the early 1980s, worker power was augmented at 207th St. because the subway system was falling apart. Yet every day, management was desperate for enough cars to run a full schedule of trains.

Under these circumstances, the shop superintendent was squeezed between union and his own upper management; cooperation with union expectations ensured that the expected quota of cars was ready to go into service each afternoon. Repairs on trucks – the wheeled undercarriage of a subway car – had to be finished early enough for them to be transported across the shop by overhead crane operators and set under the cars by a specialized crew, all of whom worked only intermittently, but always expeditiously. Work underneath the car needed to be complete before it could be “dropped” back onto the trucks; then, another specialized crew had to hook up and test the compressed air and electrical systems linking these two components. Any delay in this “assembly line” of the production of repaired subway cars could throw sand in the gears. What the union defended was the right to not be assigned other work when the picked job was complete.

This is what union democracy and industrial democracy looks like on the shop-floor – it is a highly participatory activity because workers learn that their involvement very concretely affects their working conditions. The steward or the shop chair are their representatives, but need their backing – their willingness to act – for their words to have power. But for workers to continue to support these practices, it is important that they win (at least some of the time), understand the stakes and the reasons for any sacrifices, and not bear (at least not too often) onerous additional costs for demonstrations of resistance. One of the most important skills of any shop-floor trade unionist is to gauge the temper of the workers they represent. How much can you ask of them?

Elsewhere in Transit

That kind of dialogue between workers, stewards, and the union committee was also crucial in bus depots. The depot officers’ access to both drivers and mechanics gave them power to either shut down service or, alternatively, make depot management look good to their bosses in trying conditions.

One morning, operators could suddenly “discover” a safety defect on half the buses in a depot, and invoke specific Federal regulatory standards that prohibited their use; parts to repair them could suddenly be difficult to find and laborious to install. Another afternoon, every operator could consistently hit every red light, slowing service to a crawl. Mike Tutrone recounted how he was schooled by his depot chair. As a probationary worker he was scolded for driving an unsafe bus: he was told the union would have his back if he refused to drive it. But, in the midst of a blinding snowstorm, the same officer asked him to drive a bus without a windshield across 14th St. during afternoon rush to get people home from work. In buses, one hand washed the other in a very immediate way.

Driving a bus in New York is grueling work, but the union’s ability to punish and reward managers made day-to-day life easier. A good depot chair with a cadre of route stewards could secure overtime work, gain precious extra vacation and holiday slots, defend favorable repair quotas, informally switch shift times and days off to prevent “time and attendance” disciplines, and negotiate with depot managers about assessment of fault in accidents.

Interestingly, train operators have much less power to affect their working conditions even though an individual operator, angry about mistreatment, can stall not only their own train, but a half dozen behind it; several, working collaboratively, can throw a whole line into chaos. But this operational power was coupled with an organizational weakness. An operator and conductor team work alone, and they see only a handful of co-workers at their terminal at the beginning and end of each “run.” Even when natural leaders emerged, they were on the road most of the time, while the Local has never believed a single terminal is big enough to justify a full-time union officer’s organizing presence. So, a worker who needed a favor or was in trouble most often dealt with management alone. Both individual resistance and individual deal-making were prevalent. Action by a whole terminal crew was possible: on two very rare occasions in 1983 and 1992, the whole system spontaneously exploded in a matter of days over management missteps, hundreds of trains crept down the tracks, and Transit management hastily sought to defuse the precipitating bombs it had thrown. RTO workers remembered these incidents but they were hard to replicate; mostly, they just festered.

Sometimes union presence mattered less than work structure. Most of the Maintenance of Way workers who repair the system’s physical, mechanical, and electrical infrastructure are hired with trade skills, and come to Transit with the pride of craft and the cohesiveness that goes with it. They mostly work in teams or crews too small to warrant direct supervision, left alone to do the job as they saw fit. This “recognition of [their] personhood” was a key distinction between them train operators. Based on historical experience and group norms, they had clear expectations about the appropriate amount of work per shift, and brokered informal agreements with foremen: get your work done and you can come back to the crew quarters.

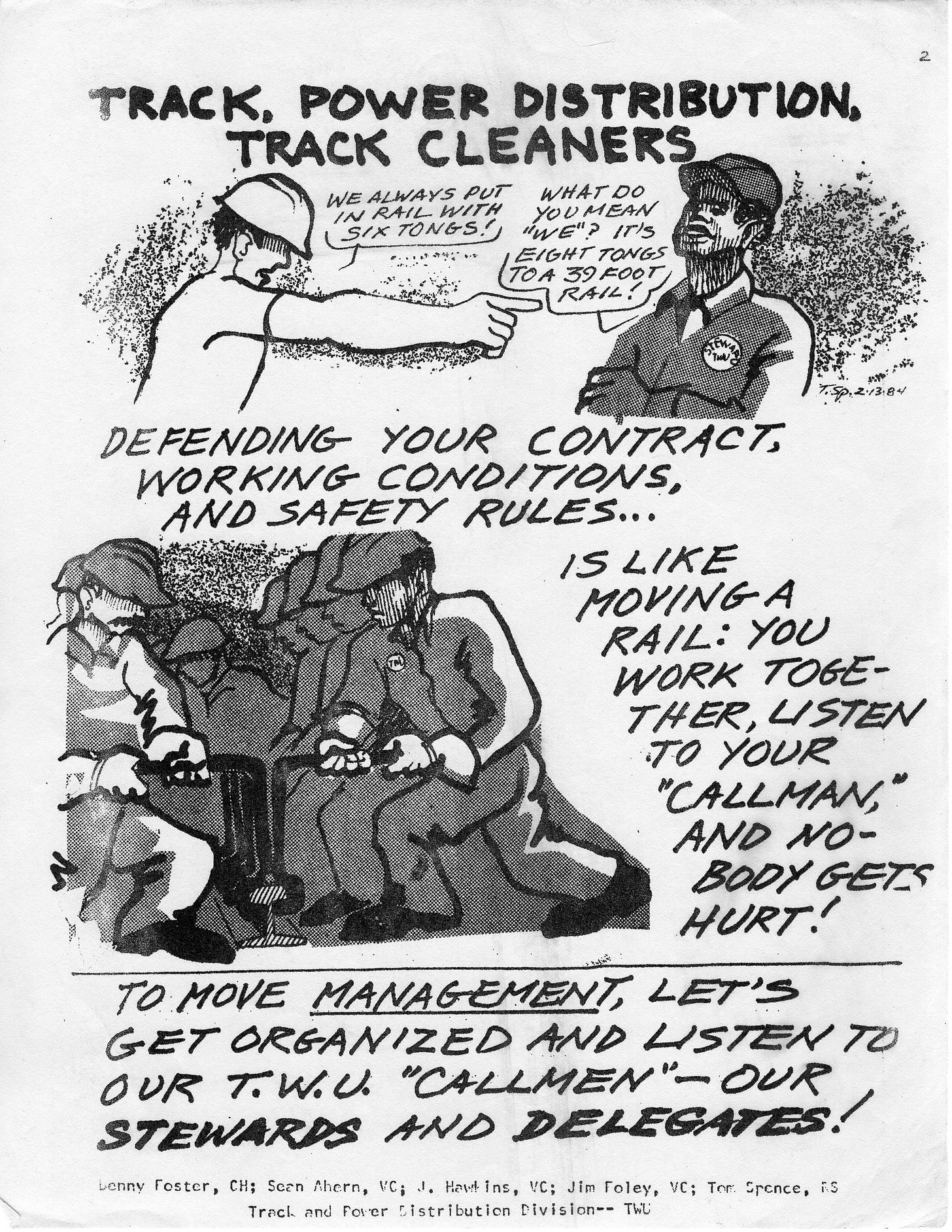

Of course, this might degenerate into choosing speed over safety, particularly in larger, supervised, Track crews where management was especially eager to get work done so trains could resume normal service. A common Trackworker motto in the 1980s was “get it and go” – maximum speed, followed by time back in the crew quarters, a leisurely lunch, or even allowing workers to go home right from the job site – that is, an hour or so earlier. That might convince a crew to work even if there were not enough rubberized mats to completely cover a live 600-volt third rail at a worksite, rather than wait around for more to be brought. Normally, 16 workers were utilized to lift a 1,300-pound rail, but perhaps it could be done by twelve? Because of

slip hazards and live electricity, work in the rain is among the most dangerous aspects of the job, but management would always want a job “closed up” before stopping the work, so that trains could pass through. A cooperative crew would be sent back to their quarters for the rest of the shift as a reward, while an uncooperative one would be sent to another job site. So exactly how hard did it have to be raining before the crew decided to stop work? Would work start before “flagging” to alert oncoming trains was completely set up, or continue as the flagging was broken down? After all, on most days – indeed, almost all days – no one died or even got injured when safety protocols were bent or broken.

Management Backlash…

Beginning in the mid-1980s, following national trends, top Transit management launched a sustained effort to roll-back worker control. A moribund union leadership mostly went along. They sabotaged a months-long slowdown meant to defend worker control at 207th St., allowing Transit to break union power there. They agreed to incorporate a “zipper clause” into the contract, letting Transit unilaterally void decades of informal “handshake” reciprocity agreements. In less-supervised work crews, that meant more rigorous work quotas. In buses, it meant the return of split shifts and less union input in assessing whether an accident was “preventable.” The union agreed to surrender the shape-up rights of 3,000 subway mechanics in return for a four percent raise. That allowed supervisors to wield carrots, but especially more and more sticks, to speed-up work and victimize troublesome stewards and activists.

Alongside the withering of shop-floor power came a loss of imagination about what might be remedied. Many transit workers resigned themselves to having little or no say in the organization of work. Even though a more militant, leadership took office in 2001, their first pre-bargaining survey showed half their members rated fixing the sections of the contract where most shop floor rules were spelled out, 10th or lower of 12 categories of demands. One new union officer bemoaned that members “had almost no expectations, so they concentrated everything on the raises. But what were the givebacks for the raises? It didn’t get into the marrow of union members that contracts are about more than numbers.” To return to my first post on workers’ control, they had come to expect “‘things’… wages… amenities, pensions, etc. dispense[d] from on high to individuals maintained in their dispersion” rather than new tools that might enhance the possibility of exercising “workers’ sovereign power.”

… and Union Ambivalence

The responsibility to change those expectations thus fell on those new union leaders. They needed to prioritize contractual remedies hemming in or eliminating the management rights clauses of the contract, and legitimizing anew all existing “past practices.” They needed to build a network of strong stewards and provide unconditional support to work crews who took direct action to address work disputes. After two decades of defeats, they had to encourage workers to believe they had power, could take initiative, and become agents of their own destiny.

In their first years in office, the new leadership wrested some gains from Transit. An undoubted success was a new contractual provision allowing workers to halt a job if they felt it was unsafe without facing disciplinary consequences. Other efforts proved more half-hearted. The union trained a thousand new stewards, but then used them mostly as errand boys rather than guerrilla fighters. Attempts to provide them with greater institutional authority faltered. The failure to restore seniority rights and protections to those 3000 mechanics revealed a disinterest in re-building the worker-led shop floor power necessary to wage fights about work conditions.

The dilemma of prioritizing fights for greater workers’ control – or to more explicitly include white collar workers, worker autonomy from dictate and micromanagement – is that most workers have given up on gaining more of it, except by individual and semi-surreptitious means. Since unions are anyway disinclined to think about the daily problems of the shop floor, it’s easy for them to abandon the fight for what workers do not seem to demand of them, and management is so loathe to concede. In Transit, to change union and workplace culture to reassert the primacy of workers’ control undoubtedly would have been difficult in the face of stiff management resistance. Although the union’s new leaders were far more ambitious and vigorous than the moribund ones they replaced, too often their disinclination to encourage spontaneous rank-and-file agency and activity was similar. Ultimately, that doomed most top-down efforts too. As British labor academic Richard Hyman has pointed out, a “radical conception of the objectives (at least potential) of unionism” is likely to fail if not accompanied by “independent initiative and momentum from below.”

If this is a vicious cycle, though, it should be possible to imagine how a virtuous cycle might take its place, in which successful fights for control, or autonomy, spark more demands for them, and then more collective organization to achieve them. That’s what David Montgomery meant when he wrote that “spontaneity and organization are not mutually-exclusive polar opposites. They are dialectically inseparable.” Workers who took on their bosses “were those who felt themselves part of strong unions, unions which could realistically be aggressive.” At Local 100, such a turn, in the face of prior history and practice, would have required deciding it was important enough to provide the resources, time, and energy that are such precious commodities for any union.

Concrete and measured analysis — clears the clutter and gets down to brass tacks.