Workers’ Control… or Things?

Eight hours of work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what we will

The sentiment behind this 150-year-old slogan remains perfectly legitimate today. Yet the fight for more time for “what we will,” and the means to enjoy that time, obscures asking questions about the eight hours (or whatever the number) at work. If work is entirely a burden, how does that shape our lives? Could work be better, more humane, more civilized? And, if so – and I answer affirmatively – how much attention and effort should we as workers, and as unions, devote to making it better? I think, a lot, although control of the workplace is what management is most loath to cede.

Largely, though, the demand variously called workers’ control, or industrial democracy, or autonomy at work, has been put on the back burner by unions, and for decades. For example, look at what the UAW’s Shawn Fain, one of the more progressive union leaders, said were the, “four core issues [that] define what it means to live and work with dignity: a livable wage, affordable healthcare, retirement security, and time to enjoy life beyond the job.” [My italics.]

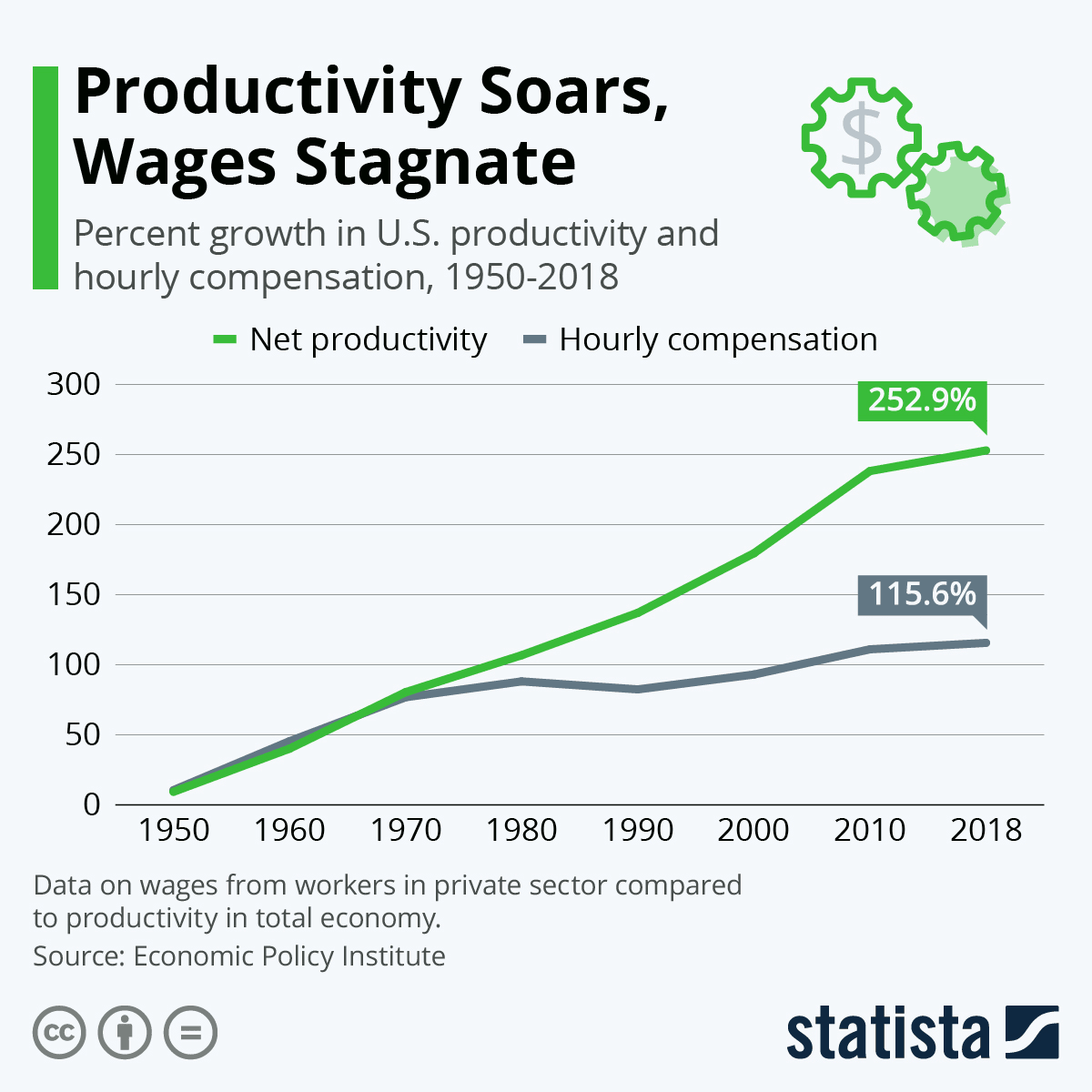

Where, exactly, is “work with dignity” on Fain’s list? Perhaps its absence is not surprising because it was the UAW that famously – or infamously – signed the 1954 “Treaty of Detroit” in which GM agreed to raise wages and benefits more or less in line with productivity increases, and the union allowed management control of the workplace, enabling that productivity. Accepting the premise that workers could be disciplined or fired for slowing or stopping production when management sped up the assembly line, neglected safety, or simply abused workers, the UAW progressively stripped its members of the tools necessary to challenge how work was organized. [1]

Despite worker dissatisfaction, “management rights clauses” – in which all rights to organize production save those specifically protected in contracts were given to management – spread throughout industry. Of course, as workers on the shop floor were demobilized, management had less to fear when it broke its side of the bargain to maintain wage-productivity parity.

In my view, though, the Treaty would have been a bad bargain for workers even if it had stuck.

In the early years of the UAW, explained one shop steward, “the steward was the Union, he was the Contract. Everything he did was decisive in the plant.” The UAW was actually initially organized more around issues of increasing workers’ control and decreasing management authority, than wages. “Now he is a Philadelphia lawyer. It’s embarrassing. Time and again management does things that I know it has a right to do under the [contract]… But the men don’t know it. If I explain to them that the company has that right under four or five rulings made previously, they get sore at me. They will say, ‘you don’t represent us; you represent the company.’ As a result — in our set up, and I’m sure it’s true elsewhere — the stewards… instead of being real leaders, tend to become more and more political fakers.”

Or, as Martin Glaberman – an autoworker, communist, and labor historian – put it, the steward became a “contract policeman” for the company, telling workers: the contract allows them to do that. Even more demobilizing and demoralizing is when management is clearly violating the contract’s terms yet the steward’s suggested recourse is to submit a grievance, which will be resolved in someone’s office, far away from those workers, or often never.

As workers reconciled themselves to this state of affairs, key elements of union power were abandoned, participatory democracy withered, workers lost confidence in their own abilities, and the remaining shop floor activists became ever more reliant on the help and goodwill of leadership and staff. Most workers came to accept the “business” or “service” union model in which they lack “shopfloor” agency – the ability and right to act – even as they grumble about the quality of the service. And they came to accept what David Montgomery called, “the cult of the expert” – whether that expert came from the union or management. A vicious circle of union decline ensued.

The dilemmas of who, and how, to fight, and who makes those decisions, are thus clearly linked. So is the problem of how to reverse this trend line in a way comprehensible to potential activists and workers who will have to make this change.

Worker’s Control as an Alternative

“For the socialist movement,” wrote Andre Gorz, “the workers' sovereign power to determine for themselves the conditions of their social participation… the content, development and social division of their labor is as important, if not more so, than ‘things’… wages… amenities, pensions, etc. dispense[d] from on high to individuals maintained in their dispersion, and impotent with respect to the process of production and relations of production.”

I love that phrase, “workers’ sovereign power.” Of course, exactly what sovereign power means will differ by workplace and occupation. You know your work better than I do. But at a minimum, it means more worker say in how production – whether of automobiles or educating students – is organized, in hiring and firing and promotions, in allocation of the work. It means limiting management’s carrots and sticks. It means legitimating the worker’s voice, responsibility and authority, and giving workers more tools to help themselves. Be imaginative: think about what it might mean where you work, how you would reorganize work.

Enhancing workers’ sovereign power should be in the forefront of all we try to do, for at least three reasons. First, obviously, the eight hours of work should be more humane than it is, and even joyful. Marx writes about how capitalist production is “alienating.” We lose our connection (more or less, depending on the work) with what we are producing and the object of production (besides the employers’ profit). More workers’ control = less alienation.

Second, as opposed to “things… dispensed from on high,” which make us into passive recipients, the struggle for more workers’ control over production, and then the decisions necessary to implement it – how should be work be organized and allocated? – make us more conscious and holistic human beings. Paulo Freire writes,

the ordinary person is crushed, diminished, converted into a spectator, maneuvered by myths which powerful social forces have created…. A fundamental human necessity [is] responsibility, of which Simone Weil says: ‘it is necessary that a man should often have to take decisions in matters great or small affecting interests that are distinct from his own, but in regard to which he feels a personal concern.’

And Staughton Lynd adds, “there must take place the transformation of the actor as well as the accomplishment of the act. Workers’ control is beautiful… because it can only come about by the creation of human beings capable of administering it.” [2]

Third, it reminds us that there were once unions, and activists, whose “philosophy… was that management had no right to exist.” Toni Gilpin’s Farm Equipment Worker stewards engaged in constant "extra-contractual shop floor activity,” wielding the contract "in the workers' defense, employing it when it [is] useful, abandoning it when [it] is not.”

So, apparently, the steward doesn’t always have to be a contract policeman – but all this involves, at a minimum, great and difficult changes in the cultural pre-dispositions – the imaginations – of both union leaders and members. Both have to decide that alongside things – wages, benefits, more vacation – we should fight for power, and agency, in the place we spend most of our waking hours.

Next: What holds us back from imagining workers’ control; and the consequences

Two Book Recommendations

Writing about workers’ control makes me think of Jack Metzgar’s great book Striking Steel, about his father, who worked at US Steel in the 1940s and 1950s. It was absolutely true that Johnny Metzgar, a hothead and shopfloor militant, enjoyed the “things” the union had won: the wages that let him buy a car and a boat and the vacation time when he could haul it north and fish. But Johnny’s workday life revolved around his efforts as a steward, when being a steward meant organizing his crew to maintain, and maybe expand, their sovereign power, as management sought to diminish it. Metzgar recounts the months-long 1959 steel strike, waged by workers to successfully retain Section 2(b) of their contract which limited management’s right to unilaterally cut staffing on jobs or introduce new machinery without bargaining with the affected workers. In the second half of the book, Metzgar recounts how that power was effectively lost, and ponders the changes in the national psyche, that made Johnny, in retirement, turn against the union movement of which he had once been such a vital part.

For pure escapism, I found Joseph Kanon’s Leaving Berlin a fine spy novel, with none of the false notes or absurdities that lesser writers use to advance their plots. August Meier is a noted writer and communist who fled Nazi Germany in 1933 for the United States. Now it’s 1949 and he’s about to be deported for refusing to name names in front of the House Unamerican Affairs Committee. The East Germans invite him “home,” but he cuts a deal with the CIA to keep his ears open and relay gossip, hoping to return to his family in the States. Soon enough, each side wants more and offers less in return, the dangers mount, and Meier is dancing his way through an increasingly intricate set of pressures and counter-pressures. When you get to the end, you’ll laugh: the final scene is a wonderful riff on one of the classics of the genre.

[2] Staughton Lynd, “Workers’ Control in a Time of Diminished Workers’ Rights,” Radical America 10, no. 5 (1976).

[1] Nelson Lichtenstein, "Life at the Rouge: A Cycle of Workers' Control" in Life and Labor: Dimensions of American Working-Class History (1986): 237-59.